Suggested reading:

THOMAS EDISON MEETS HIS BASTARD SON, a short story from the BOOK O’KELLS.

Suggested listening:

DEARBORN audio short story from the novel NATURE OF THE BEAST from the BOOK OF O’KELLS.

History is disappearing. Facts are long-gone.

Instead of sticking to what happened, anyone with a quill enjoys the liberty to make up history as they go along—picking nits as they suit one’s particular body politic. How then to make sense of the evergreen popularity of historical fiction in a dystopian, ahistorical world?

Instead of sticking to what happened, anyone with a quill enjoys the liberty to make up history as they go along—picking nits as they suit one’s particular body politic. How then to make sense of the evergreen popularity of historical fiction in a dystopian, ahistorical world?

History and fiction really have nothing much to do with each other, but stitch them together and you’ve got a fictive genre suitable for endless hashtags and haberdashery. Historical fiction transports the reader from what actually happened to whatever suits the writer. You can buy into the world he/she/we/they are making without ever admitting the real world lays elsewhere.

Me? I love history. I won the history award in eighth grade and won another one as a senior in high school—and those awards still matter to me. I graduated with a degree in history and then I became a journalist to edge as close to history as I could get. But I also became a writer of fiction, paid (or not) to make things up. As I wrote my way into novels I was inspired by the historical legerdemain of E.L. Doctorow in Ragtime, a book replete with fictional characters like Emma Goldman, Henry Ford, Harry Houdini, Booker T. Washington, Evelyn Nesbit, and J. P. Morgan.

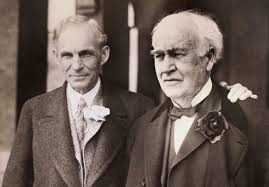

Ford and Edison Come To Life

I too have taken on Henry Ford in the audio version of Dearborn from my forthcoming novel NATURE OF THE BEAST, the origin story for my six BOOK OF O’KELLS novels. Ford’s close friend Thomas Edison is even more important to my O’Kells stories because he is the father of Jake O’Kell, a key character in my fictional family saga. The aforementioned short story—THOMAS EDISON MEETS HIS BASTARD SON—shows the challenges (for me at least) when a famous character suits up in a novelistic greatcoat.

As an amateur historian I read from the historical record though without the exhaustive appetite for research many writers bring to historical fiction. Instead I was looking for Edison’s essence—and I found his voice his own writing. Check this out from THOMAS EDISON MEETS HIS BASTARD SON, taken directly from Edison’s prose, but now in the context of unknowingly meeting his bastard son for the first time:

“What a sleep I had, son—slept as sound as a bug in a barrel of morphine. Slept splendid. Evidently I was inoculated with insomnic bactilli when a baby. Are you a dreamer, son? I dreamed that I was in the depth of space on a bleak and gigantic planet with the solitary soul of the great Napoleon as the sole inhabitant. I dreamed he was amid the howl of the tempest and the lashing of gigantic waves high up on a jutting promontory, gazing out among the worlds and stars that stud the depths of infinity. Miles above him circled and swept the sky with ponderous wing the imperial condor, bearing in his talons a message —”

The boy followed the great big man’s eyes upwards, as though he too might see a condor or two —

“—then the scene busted—thought I was looking out upon the sea. Suddenly the air was filled with millions of little cherubs as one sees in Raphael’s pictures. Each, I thought, was about the size of a fly. They were perfectly formed and seemed semi-transparent. Each swept down to the surface of the sea, reached out both their tiny hands, grabbed a very small drop of water, and flew upwards, where they assembled and appeared to form a cloud.”

“Really?” the boy said.

“Just what I dreamed up,” the great big man said.

This is Thomas Edison recounting an actual dream in prose, but in my novel his own words have the advantage of both invoking a dream-like state and creating an indelible tone for the made-up Edison based upon the real one.

There is not a writer alive, immersed in research or not, who could write this sentence—“Evidently I was inoculated with insomnic bactilli when a baby”—other than Edison himself. But once I stole the tone from the great big man, I had to fake it from that moment on. Once the shoe fits, the writer of historical fiction has to wear it:

“Me ready to spit and not a spittoon in sight! I don’t believe in the damn things anywho. There’s never a spittoon around when a man needs one, you know. It’s a proven scientific fact. Why I’ve run a few experiments on it myself—whenever I need to spit, that is.”

A stream of his nicotinny spit hit the spine of The Holy Bible on the floor of the closet.

“A man who has to swallow his own spit is a man without freedom,” the great big man said. “And a man without freedom ain’t worth a spit.”

The lesson here to me is the power of Thomas Edison’s voice as a window into the psychic, mythological, historical world he inhabited. The novelist gets an extra bump because Edison invented sound recording for the masses, so hearing his voice in prose is even more poignant. His words really do matter.

When it comes to historical fiction, the writer had best measure twice and cut once. You can’t make this stuff up, even though you have no choice.